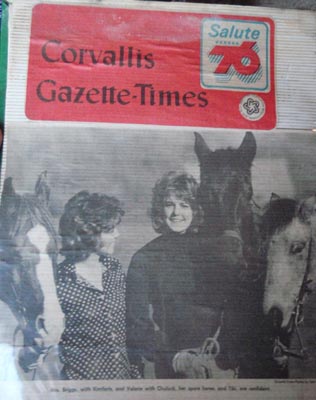

A profile of Valorie Briggs, Tiki and Chuluck: competitors in the 1976 Great American Horse Race

When you're young and infatuated with horses, nothing seems unattainable. You can do anything. Like ride all the way across the United States, from New York to California.

"I was always horse crazy. Always," says Valorie Lund (back then she was Valorie Briggs).

"We had a horse named Ginger that Mom would put us up on for our naps every day, to get us out of the way, so I literally grew up riding before I could walk. And I rode all the time. That was our whole entertainment growing up in Oregon - we would ride. We rode, incessantly, and we did crazy things on horses."

Now a Thoroughbred racehorse trainer from Phoenix, Arizona - with one of the top sprinters in the country, Atta Boy Roy - in the 1970's she was just a teen-aged horse crazy rural farm girl from outside of Philomath, Oregon.

"I always rode with a big coat on. When you wanted to go somewhere, and there was a fence in the way, you'd lay your coat over the top strand of barbed wire. That way your horse could see it well and it was there in case he clipped the wire, and you'd jump the barbed wire fences. We swam our horses down rivers. My middle sister Leslie and I would tag team deer. The game was to see if you could get close enough to touch them. You'd jump logs, you'd jump fences, all bareback. We always rode bareback. The folks wouldn't let us ride with saddles, because if you came off, at least you came off clean, you weren't going to get hung up somewhere."

Valorie's sisters and cousins would play Riding School. One person would play the riding instructor; the rest would play students. "The students would try to make it hard on the instructor. You'd get on backwards, kick your horse into a run, and start screaming, so the instructor had to run you down and catch you and get you put on your horse correctly. Or you'd uncinch your saddle (if you were riding with one), and let the horse run off, and see if you could jump things without a cinch. We all got to where we could get on and off, step into a saddle without turning the saddle with the cinch unbuckled.

"We were wild terrors on horseback. But that was all of our entertainment."

Main accomplice in her escapades of terror was a little buckskin mustang-Arabian cross, no bigger than 13 1/2 hands. Valorie broke him herself when she was around 10 or 11 years old. "Tiki went just about anywhere, did about anything. But - he was ornery!" Valorie shakes her head and laughs, still vividly recalling his antics 35 years ago. "He was really ornery! He was too smart for his own good. He'd do what you wanted... if he felt like it."

One time, Tiki readily loaded up into a Volkswagon van for her dad and uncle. Valorie is still amazed and amused at that sight: "So they're driving down the road, and they got a horse's head between two guys in the front seat, and they're going fishing!"

That horse had a definite sense of humor. "You could do pole bending with him, and as soon as you were leaning one way, he'd duck out the other way and drop you.

"Pretty much any place you wanted to go, he could either jump over and get in, or crawl through, or crawl under. He could literally get you anywhere.

"He was like a big dog. BUT. if he didn't want to do something? You know what? He wasn't going to do it. But he was amazingly athletic."

Valorie's mom Mary Lou agrees. "I saw Valorie take that horse over logs. There was a section up near our farm where a guy ran cattle, and he didn't fence it because there were all those trees down. But Valorie'd walk that horse up and down those logs, all the time. He didn't believe there wasn't no place he couldn't go."

Valorie was 16 years old when she saw the article in the Western Horseman magazine announcing the 1976 Bicentennial Great American Horse Race. A 3200 mile, 99-day horse race across the United States, from Frankfort, New York to Sacramento, California, might sound daunting to most people. But not to a horse-obsessed girl who lived on Tiki's back. And Tiki was one of the main reasons Valorie knew she wanted to do it. "'Oh my goodness,' I thought, 'there's no horse tougher than Tiki! If anybody can do it, it would be him!'"

It would be a challenge, but the physical and mental endurance that would be needed for such a ride wasn't anything she wasn't familiar with. Valorie had learned endurance riding from Elwin Wines, who finished the 100-mile Tevis Cup ride three years in a row, from 1970 to 1972, and was the 1975 National Endurance Ride champion. He taught Valorie what he knew about the fledgling sport of endurance. Valorie crewed for him, then rode a few endurance rides herself. With that, and her practically living in the saddle anyway, the Great American Horse Race was a natural progression.

The only thing intimidating about the race was the steep $500 entry fee. "That was a lot back then," says Valorie. "I showed my mom and said 'Oh man I'd really like to do this, but it's $500 to enter'. Mom said 'You know? If it's something you really want to do, we'll figure out a way to do it.'"

And they found a way. Valorie went around town and got sponsors. They got their truck, their horse feed, and the truck camper sponsored. All Valorie needed now was one more horse (riders were allowed two mounts; both mounts had to be on the trail all the time - one ridden, one ponied - or time penalties were assessed).

She and her mom went looking for "a tough horse that could do a lot." They ended up on a ranch in eastern Oregon where Valorie tried out 9-year-old Chuluck, a bay Thoroughbred cross who'd been wild for his first 4 1/2 years. At the time Valorie was told he was half Arabian, although in retrospect she doubts that.

Chuluck was saddled up for her. "He had a long spade bit on him, and a tie-down. They had one of the cowboys get on him and ride him around first a little bit. He'd freeze up, then he'd sky leap, but you'd never know which way he was going to go. I figured out later if you'd just let him go, he'd be okay, but if you tried to ease him down, slow him down, he'd explode. He was a pretty wild horse..."

Valorie rode Chuluck for the first time that day on an all-day roundup.

A pig roundup.

The rancher planted potatoes on top of the mountain, and when he was done digging up the potatoes, he turned pigs out to root up the rest and scour the acreage. When they were done, ranch hands would round up the pigs on horseback. It wasn't easy. "The pigs would hide, and they'd shoot out of the brush just like quail in every direction." Valorie like the spunk and athleticism of Chuluck, and ended up buying him for $500.

She was set. Plans were laid; training commenced. Valorie worked on getting herself and her horses in shape for riding 6 days a week, 45-70 miles a day, through all kinds of weather, for over 3200 miles.

And Valorie wasn't going just to ride in the Great American Horse Race: she believed she had a good chance of crossing the finish line first. There was an enticing $25,000 purse awaiting the winner in Sacramento. "If I didn't think I had a good chance of winning," she said in a pre-race interview, "I wouldn't enter." And she believed she had the best horse in Tiki. "Tiki is far from beautiful," she said back then, "but he is a good horse for endurance."

In April of 1976, Valorie, her mom Mary Lou - who also started the Great American Horse Race on an Arabian stallion named Kimfaris, her father Lester, her grandmother, one of her older sisters and her brother, and three horses loaded up for the drive from Oregon across America to the start of the race in Frankfort, New York.

A teenager, her smart 8-year-old half mustang and her 10-year-old ranch horse... and the whole of a country to conquer.

"At least we'll be able to say we've done something almost nobody else in the world has done before."

Next: Part 2

No comments:

Post a Comment